What's Anycast and why would I use it?

Recently I’ve heard some confusion as to what Anycast is, ranging from it being part of the IPv6 specification to multicast.

While I’m not a network dude, hopefully this post will give you an overview of what Anycast is, how it’s useful and what to watch out for.

Overview

Firstly to clear up some confusion, Anycast is not a protocol (TCP/UDP) or protocol version (IPv4/IPv6), but a type of addressing such as Unicast or Broadcast.

As far as the ‘client’ is concerned, they are talking unicast (to a single node), but this may be routed to one of many nodes depending on the routing table.

A quick example of this happening can be seen if you traceroute to an Anycast IP address from different locations in the world as seen below

traceroute to ian.ns.cloudflare.com (173.245.59.118), 30 hops max, 60 byte packets

1 router1 (10.44.200.254) 15.334 ms 17.279 ms 19.183 ms

2 host-92-23-160-1.as13285.net (92.23.160.1) 29.204 ms 32.556 ms 36.016 ms

3 host-78-151-225-101.static.as13285.net (78.151.225.101) 38.386 ms 40.704 ms 42.598 ms

4 host-78-151-225-84.static.as13285.net (78.151.225.84) 63.415 ms xe-11-2-0-bragg002.bir.as13285.net (78.151.225.72) 44.347 ms 46.697 ms

5 xe-11-1-0-rt001.the.as13285.net (62.24.240.6) 49.117 ms xe-11-1-0-rt001.sov.as13285.net (62.24.240.14) 51.454 ms 54.374 ms

6 host-78-144-1-61.as13285.net (78.144.1.61) 56.102 ms 48.605 ms 41.366 ms

7 host-78-144-0-180.as13285.net (78.144.0.180) 42.400 ms host-78-144-0-116.as13285.net (78.144.0.116) 39.599 ms host-78-144-0-164.as13285.net (78.144.0.164) 37.310 ms

8 195.66.225.179 (195.66.225.179) 38.239 ms 73.818 ms 72.494 ms

9 ian.ns.cloudflare.com (173.245.59.118) 38.989 ms 37.828 ms 38.971 ms

traceroute to ian.ns.cloudflare.com (173.245.59.118), 30 hops max, 60 byte packets

1 router1-dal.linode.com (67.18.7.161) 19.229 ms 19.291 ms 19.392 ms

2 xe-2-0-0.car03.dllstx2.networklayer.com (67.18.7.89) 0.197 ms 0.220 ms 0.202 ms

3 po101.dsr01.dllstx2.networklayer.com (70.87.254.73) 0.513 ms 0.537 ms 0.624 ms

4 po21.dsr01.dllstx3.networklayer.com (70.87.255.65) 0.902 ms 0.983 ms 1.020 ms

5 ae16.bbr01.eq01.dal03.networklayer.com (173.192.18.224) 16.145 ms 16.138 ms 16.112 ms

6 141.101.74.253 (141.101.74.253) 0.602 ms 0.566 ms 0.549 ms

7 ian.ns.cloudflare.com (173.245.59.118) 0.523 ms 0.670 ms 0.493 ms

Note that the DNS (ian.ns.cloudflare.com) resolves to the same IP (173.245.59.118), but the traffic goes to different routers (141.101.74.253 vs 195.66.225.179).

The ‘magic’ here happens at the routing layer, a router will have multiple ‘paths’ to the IP (173.245.59.118) and chooses the best one based on its metrics.

A large (public) example of Anycast being used is the root nameservers - combined there are something like 13 (v4) IP addresses serving NS entries, with ~350 servers behind those 13 IPs distributed throughout the world.

For those used to dealing with internal networks

Imagine you have 3 offices configured in a L2 triangle for redundancy:

Your gateway is England, Scotland and Wales need to access it if either of their links fail. You also have servers in each of the offices and want to access them as fast as possible.

Keeping the links at layer 2 and blocking one (via something like STP) would give you gateway redundancy - if link A failed, link B would unblock and start forwarding traffic.

The problem here is you are having to go via Scotland to access Wales from England, when they have a direct link. You can’t have both links up because you’d cause a loop and no traffic would pass.

The solution is to make both links layer 3 and use a routing protocol to advertise the ranges over the top of them - there are reasons you’d want to use layer 2, or have one layer 2 and one layer 3, this is outside the scope of this example though.

I’m not going to get into how to configure a routing protocol - there are a few to choose from, for this use case it doesn’t hugely matter. Let’s assume both links are the same speed and are direct (1 hop away).

The topology looks something like

This means if any of the offices want to talk to another office, they are only 1 hop away and don’t have to go though a middle man gateway - but if the direct link fails, they can be re-routed the long (2 hops) way around.

In summary using routing between the 3 offices allows for transparent fail over and best-performance access. In a more complicated topology this is very useful.

Essentially, this is also how ‘Anycast’ works - the main difference being is we’re dealing with multiple nodes, rather than just re-advertising a single node (route). The routing doesn’t care either way - it will choose the ‘best’ path based on what it knows about.

Why is this useful?

Anycast gives you a number of benefits such as

- Higher reliability/availability

- Higher performance

- Localisation/migration of DoS/DDoS attacks

- Client agnostic

Why doesn’t everyone use it?

There are some drawbacks to using Anycast addressing

- Can be complex to deploy - requires an AS, addressing/routing management, more routes being advertised

- Can be expensive - IP space, network infrastructure, training

- Harder to troubleshoot

- Harder to monitor

How would I use it?

One of the most common use in for DNS services, however any stateless protocol can take advantage of Anycast - it is possible to use stateful protocols, however you need a much higher level of control and risk ‘breaking’ connections across 2 nodes.

Imagine you where serving users out of Europe, US and Asia-Pacific.

A common thing to do would be create 3 NS entries pointing to servers in each location

myawesomedns.something. 360 IN SOA ns1.myawesomedns.something. root.myawesomedns.something. (1303702991 14400 14400 1209600 86400)

myawesomedns.something. 360 IN NS ns1.myawesomedns.something.

myawesomedns.something. 360 IN NS ns2.myawesomedns.something.

myawesomedns.something. 360 IN NS ns3.myawesomedns.something.

; EU

ns1 360 IN A 10.0.0.1

; APAC

ns2 360 IN A 192.168.0.1

; US

ns3 360 IN A 172.16.0.1

These NS records would then be “glued” on the root nameservers, so the first resolver can find the NS servers IP address.

Now there are 2 problems with this, if you loose a server the resolver (client) will be slow to fail over (probably timing out a few requests) and a user in the US might end up going to the server in APAC rather than the ‘local’ one to them.

Anycast helps to solve both these issues.

If a server goes down you can withdraw the route and (as long as you’re not flapping routes) your peers should pick it up in a few minutes.

In the case of a user making a request to the Anycast IP, the request will be routed to the ‘nearest’ node - in normal operation this would be the ‘local’ one, if that had failed it would automatically (after the route withdrawal) go to the next ‘nearest’.

Now I’m quoting ‘nearest’ and ‘local’ and these are determined by your routing protocol, normally based on metrics such as weight, hops or speed, rather than physical location.

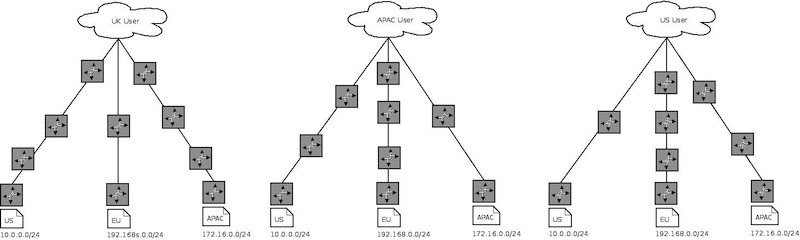

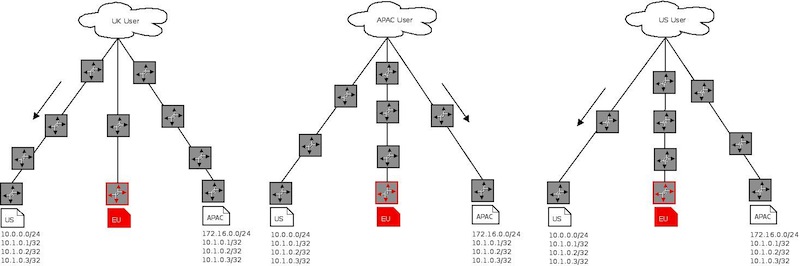

The routing before we start using Anycast

Requests to ns{1..3} (192.168.0.1, 127.16.0.1, 10.0.0.1) before we start using Anycast

So lets start using Anycast, we’re going to keep the original IPs as ‘maintenance’ IPs - ones we know only go to that single host and create a new block.

myawesomedns.something. 360 IN SOA ns1.myawesomedns.something. root.myawesomedns.something. (1303702991 14400 14400 1209600 86400)

myawesomedns.something. 360 IN NS ns1.myawesomedns.something.

myawesomedns.something. 360 IN NS ns2.myawesomedns.something.

myawesomedns.something. 360 IN NS ns3.myawesomedns.something.

; EU

srv-ns1 360 IN A 10.0.0.1

; APAC

srv-ns2 360 IN A 192.168.0.1

; US

srv-ns3 360 IN A 172.16.0.1

; Anycast

ns1 360 IN A 10.1.0.1

ns2 360 IN A 10.1.0.2

ns3 360 IN A 10.1.0.3

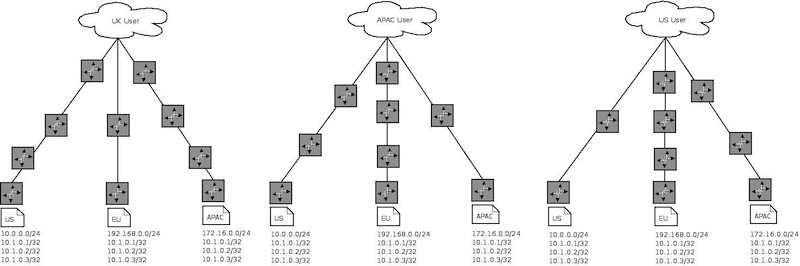

10.1.0.1, 10.1.0.2 & 10.1.0.3 now need to be advertised from the EU, APAC and US routers as /32 blocks - with no summary route for 10.1.0.0 0.0.0.255. 10.1.0.1, 10.1.0.2 & 10.1.0.3 also need to be brought up on loopback interfaces on the server and the DNS server configured to bind to them.

Once this propagates out routing will take care of sending your traffic to the right place, in the event of an outage or maintenance just withdraw the routes so they are no longer advertised and traffic will be re-routed.

This is slightly oversimplified as there is a certain level of tuning needed to stop flapping, which can cause your updates to be delayed (due to dampening timers etc).

I won’t go into the BGP configuration in this post as it’s a little lengthy to explain/draw how routing tables look, essentially you configure your neighbours and send them /32 routes - cisco have a nice example for configuring BGP on IOS. Be careful (use filters) when dealing with BGP/EGP protocols as you can do really weird things ;)

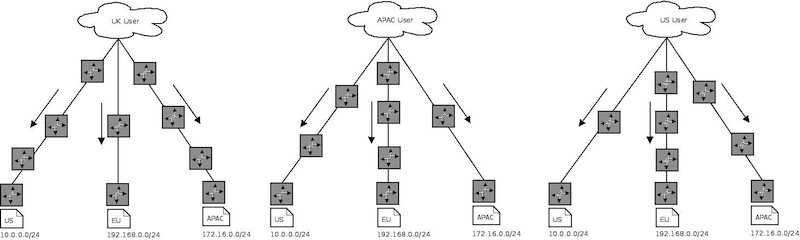

The routing after we start using ‘Anycast’ IPs

Requests to ns{1..3} (10.1.0.{1..3}) after we start using ‘Anycast’ IPs

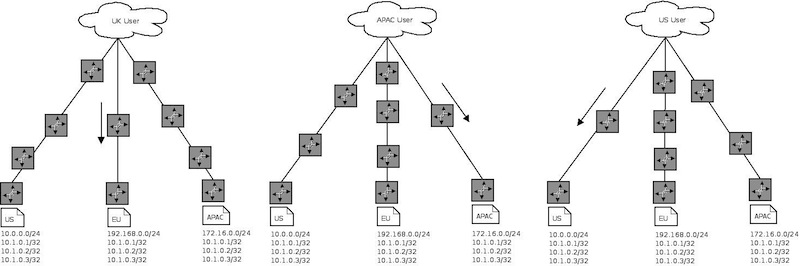

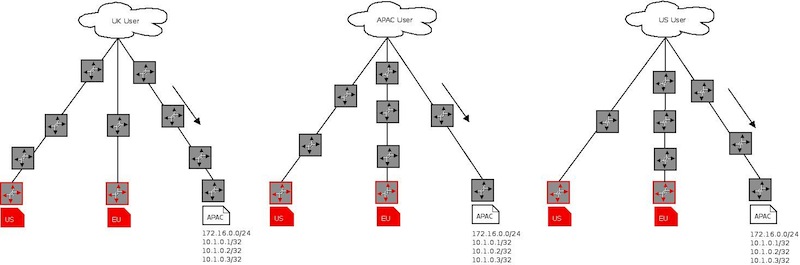

In the case of the EU site failing the routes would withdraw and requests would be re-routed

In the case of the EU and the US sites failing, requests would be re-routed in the same manner

All this happens at layer 3 - in the DNS service scenario we would probably use GeoIP logic at layer 7 to localise the response and then serve the request.

20 Jan 2013

20 Jan 2013